Hello, World!

Taichi is a domain-specific language designed for high-performance, parallel computing, and is embedded in Python.

When writing compute-intensive tasks, users can leverage Taichi's high performance computation by following a set of extra rules, and making use of the two decorators @ti.func and @ti.kernel. These decorators instruct Taichi to take over the computation tasks and compile the decorated functions to machine code using its just-in-time (JIT) compiler. As a result, calls to these functions are executed on multi-core CPUs or GPUs and can achieve acceleration by 50x~100x compared to native Python code.

Additionally, Taichi also has an ahead-of-time (AOT) system for exporting code to binary/shader files that can be run without the Python environment. See Tutorial: Run Taichi programs in C++ application for more information.

Prerequisites

- Python: 3.7/3.8/3.9/3.10 (64-bit)

- OS: Windows, OS X, and Linux (64-bit)

Installation

Taichi is available as a PyPI package:

pip install taichi

Hello, world!

A basic fractal example, the Julia fractal, can be a good starting point for you to understand the fundamentals of the Taichi programming language.

import taichi as ti

import taichi.math as tm

ti.init(arch=ti.gpu)

n = 320

pixels = ti.field(dtype=float, shape=(n * 2, n))

@ti.func

def complex_sqr(z): # complex square of a 2D vector

return tm.vec2(z[0] * z[0] - z[1] * z[1], 2 * z[0] * z[1])

@ti.kernel

def paint(t: float):

for i, j in pixels: # Parallelized over all pixels

c = tm.vec2(-0.8, tm.cos(t) * 0.2)

z = tm.vec2(i / n - 1, j / n - 0.5) * 2

iterations = 0

while z.norm() < 20 and iterations < 50:

z = complex_sqr(z) + c

iterations += 1

pixels[i, j] = 1 - iterations * 0.02

gui = ti.GUI("Julia Set", res=(n * 2, n))

i = 0

while gui.running:

paint(i * 0.03)

gui.set_image(pixels)

gui.show()

i += 1

Save the code above to your local machine and run this program, you get the following animation:

note

If you are not using an IDE for running code, you can simply run the code from your terminal by:

- Go to the directory that contains your .py file

- Type in

python3 filename.py(replace filename with your script's name. Be sure to include the.pyextension)

Let's dive into this simple Taichi program.

Import Taichi

import taichi as ti

import taichi.math as tm

The first two lines import Taichi and its math module. The math module contains built-in vectors and matrices of small dimensions, such as vec2 for 2D real vectors and mat3 for 3×3 real matrices. See the Math Module for more information.

Initialize Taichi

ti.init(arch=ti.gpu)

The argument arch in ti.init() specifies the backend that will execute the compiled code. This backend can be either ti.cpu or ti.gpu. If the ti.gpu option is specified, Taichi will attempt to use the GPU backends in the following order: ti.cuda, ti.vulkan, and ti.opengl/ti.Metal. If no GPU architecture is available, the CPU will be used as the backend.

Additionally, you can specify the desired GPU backend directly by setting arch=ti.cuda, for example. Taichi will raise an error if the specified architecture is not available. For further information, refer to the Global Settings section in the Taichi documentation.

note

ti.init(**kwargs)- Initializes Taichi environment and allows you to customize your Taichi runtime depending on the optional arguments passed into it.

Define a Taichi field

n = 320

pixels = ti.field(dtype=float, shape=(n * 2, n))

The function ti.field(dtype, shape) defines a Taichi field whose shape is of shape and whose elements are of type dtype.

Field is a fundamental and frequently utilized data structure in Taichi. It can be considered equivalent to NumPy's ndarray or PyTorch's tensor, but with added flexibility. For instance, a Taichi field can be spatially sparse and can be easily changed between different data layouts. Further advanced features of fields will be covered in other scenario-based tutorials. For now, it is sufficient to understand that the field pixels is a dense two-dimensional array.

Kernels and functions

@ti.func

def complex_sqr(z): # complex square of a 2D vector

return tm.vec2(z[0] * z[0] - z[1] * z[1], 2 * z[0] * z[1])

@ti.kernel

def paint(t: float):

for i, j in pixels: # Parallelized over all pixels

c = tm.vec2(-0.8, tm.cos(t) * 0.2)

z = tm.vec2(i / n - 1, j / n - 0.5) * 2

iterations = 0

while z.norm() < 20 and iterations < 50:

z = complex_sqr(z) + c

iterations += 1

pixels[i, j] = 1 - iterations * 0.02

The code above defines two functions, one decorated with @ti.func and the other with @ti.kernel. They are called Taichi function and kernel respectively. Taichi functions and kernels are not executed by Python's interpreter but taken over by Taichi's JIT compiler and deployed to your parallel multi-core CPU or GPU, which is determined by the arch argument in the ti.init() call.

The main differences between Taichi functions and kernels are as follows:

- Kernels serve as the entry points for Taichi to take over the execution. They can be called anywhere in the program, whereas Taichi functions can only be invoked within kernels or other Taichi functions. For instance, in the provided code example, the Taichi function

complex_sqris called within the kernelpaint. - It is important to note that the arguments and return values of kernels must be type hinted, while Taichi functions do not require type hinting. In the example, the argument

tin the kernelpaintis type hinted, while the argumentzin the Taichi functioncomplex_sqris not. - Taichi supports the use of nested functions, but nested kernels are not supported. Additionally, Taichi does not support recursive calls within Taichi functions.

tip

Note that, for users familiar with CUDA programming, the ti.func in Taichi is equivalent to the __device__ in CUDA, while the ti.kernel in Taichi corresponds to the __global__ in CUDA.

For those familiar with the world of OpenGL, ti.func can be compared to a typical function in GLSL, while ti.kernel can be compared to a compute shader.

Parallel for loops

@ti.kernel

def paint(t: float):

for i, j in pixels: # Parallelized over all pixels

The key to achieving high performance in Taichi lies in efficient iteration. By utilizing parallelized looping, data can be processed more effectively.

The code snippet above showcases a for loop at the outermost scope within a Taichi kernel, which is automatically parallelized. The for loop operates on the i and j indices simultaneously, allowing for concurrent execution of iterations.

Taichi provides a convenient syntax for parallelizing tasks. Any for loop at the outermost scope within a kernel is automatically parallelized, eliminating the need for manual thread allocation, recycling, and memory management.

The field pixels is treated as an iterator, with i and j being integer indices ranging from 0 to 2*n-1 and 0 to n-1, respectively. The (i, j) pairs loop over the sets (0, 0), (0, 1), ..., (0, n-1), (1, 0), (1, 1), ..., (2*n-1, n-1) in parallel.

It is important to keep in mind that for loops nested within other constructs, such as if/else statements or other loops, are not automatically parallelized and are processed sequentially.

@ti.kernel

def fill():

total = 0

for i in range(10): # Parallelized

for j in range(5): # Serialized in each parallel thread

total += i * j

if total > 10:

for k in range(5): # Not parallelized because it is not at the outermost scope

You may also serialize a for loop at the outermost scope using ti.loop_config(serialize=True). Please refer to Serialize a specified parallel for loop for additional information.

WARNING

The break statement is not supported in parallelized loops:

@ti.kernel

def foo():

for i in x:

...

break # Error!

@ti.kernel

def foo():

for i in x:

for j in range(10):

...

break # OK!

Display the result

To render the result on screen, Taichi provides a built-in GUI System. Use the gui.set_image() method to set the content of the window and gui.show() method to show the updated image.

gui = ti.GUI("Julia Set", res=(n * 2, n))

# Sets the window title and the resolution

i = 0

while gui.running:

paint(i * 0.03)

gui.set_image(pixels)

gui.show()

i += 1

Taichi's GUI system uses the standard Cartesian coordinate system to define pixel coordinates. The origin of the coordinate system is located at the lower left corner of the screen. The (0, 0) element in pixels will be mapped to the lower left corner of the window, and the (639, 319) element will be mapped to the upper right corner of the window, as shown in the following image:

![]()

Key takeaways

Congratulations! By following the brief example above, you have learned the most important features of Taichi:

- Taichi compiles and executes Taichi functions and kernels on the designated backend.

- For loops located at the outermost scope in a Taichi kernel are automatically parallelized.

- Taichi offers a flexible data container, known as field, and you can utilize indices to iterate over a field.

Taichi examples

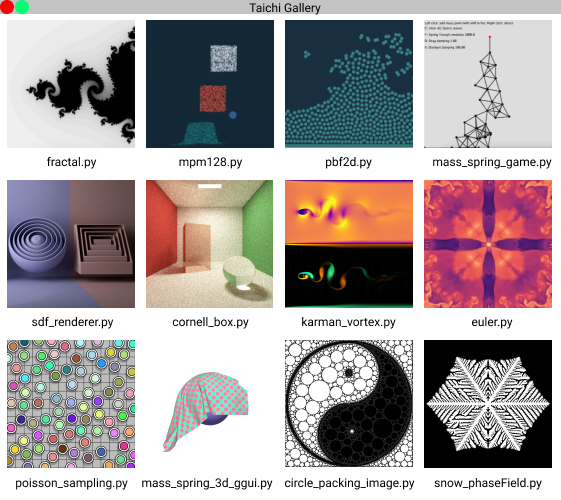

The Julia fractal is one of the featured demos included in Taichi. To view additional selected demos available in the Taichi Gallery:

ti gallery

A new window will open and appear on the screen:

To access the complete list of Taichi examples, run ti example. Here are some additional useful command lines:

ti example -p fractalorti example -P fractalprints the source code of the fractal example.ti example -s fractalsaves the example to your current working directory.

Supported systems and backends

The table below provides an overview of the operating systems supported by Taichi and the corresponding backends that are compatible with these platforms:

| platform | CPU | CUDA | OpenGL | Metal | Vulkan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Windows | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ | N/A | ✔️ |

| Linux | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ | N/A | ✔️ |

| macOS | ✔️ | N/A | N/A | ✔️ | ✔️ |

- ✔️: supported;

- N/A: not available

You are now prepared to begin writing your own Taichi programs. The following documents provide more information about how to utilize Taichi in some of its typical application scenarios: